I recently discussed my dividend growth model on this blog. As explained, I separate my portfolio into two different segments: a core portfolio where I want to keep my stocks for a long time and a dividend growth stock portion where I keep a few stocks for a shorter period like 1 to 3 years to benefit from a more powerful growth (which means more risk as well). Following this article, a member asked me in which situations would I sell my stocks. I always said buying was easy but selling (and making money) is probably the hardest part of investing. This article is about how to set the right time to sell when you are in the money and the right time to sell when you are losing money. Both situations are very different and require different techniques.

When is the Right Time to Sell When You Make Money

When should you sell a winning stock? Aren’t you afraid it will continue to go up?

Selling a stock and looking at it 6 months later to realize it is up by 20% since you sold is an awful feeling. But it will happen to you. For example, I sold Seagate Technology (STX) at $40 in 2013 and the stock is now around $55 after a peak of $61 earlier this year. Should I cry about the 52% return I left on the table (not counting the dividend!) or should I look at the 72% return I made over less than two years?

The first lesson when you sell a winning stock is to appreciate that you made money on your trade. Be proud that you selected a good company and realized a profit. Because this also happens all the time to investors; they keep their winners until they lose. I’m not the next Warren Buffet, but I’ll explain what metrics I use to sell a winner.

#1 All Stocks are Different – I Don’t Use a Maximum Return

I never sell a stock because I made 25% or 50% or whatever rule you read in books. This is because a stock has an unlimited upside power. An investor who sold Apple (AAPL) at $25 after realizing a 25% gain is probably crying every day since. You can’t expect a stock to go down because it was up for a while.

But how can you determine a selling price if you don’t set an investment return expectation in the first place?

When I buy shares to include in my dividend growth addition, the company usually doesn’t meet all my core portfolio metrics but shows a strong upside potential. The keyword here is potential; potential of a higher return or a higher loss on my investment. There is usually an anomaly with the P/E ratio or the dividend paid.

I follow these companies closely and analyze their financial results quarterly. I want to see two things:

A) Is the company is heading towards my expectations (e.g. is the potential being realized or was just a mirage)?

B) Does the company still show future upside potential (the stock may go up, and still shows it could go higher)?

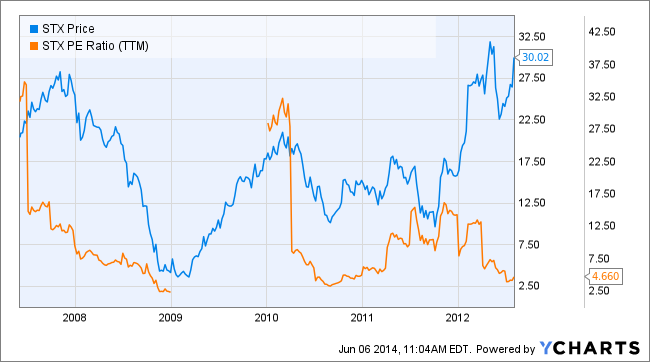

I’ll use my example of Seagate Technology (STX). I bought it in July 2012 after writing my stock analysis. The company suffered from two crises at the same time: the 2008 crash combined with a major flood in their plant in Taiwan. Therefore, in 2007, the stock was trading around $27, dropped as low as $3.61 and was back around $27 in 2012:

But the real reason why I bought the stock is not on the previous graph on the future one:

The stock dropped after STX lost a lot of money in 2009. But starting in 2010, Seagate was gradually coming back to life. The market didn’t see it that way and kept a very low valuation. When I bought the stock, the P/E ratio was around 4. I knew I was taking a risk; after all, the company wasn’t evolving in a very promising market as hard disks is a mature market with very little growth expected. However, with a 6% dividend yield and a 4 P/E ratio, I thought the company could shoot for the sky again. This is exactly what happened in the following 18 months:

As you can see, both P/E ratio and stocks continue to increase and the company rapidly gained back a more regular valuation. However, around 9-10 P/E ratio, STX started to show the perfect signs of a dividend trap. You know, those companies showing a great dividend, low P/E ratio so you think you should go in, rack-up the dividend and wait for the upside during a new valuation of the stock?

I’m saying that because sales were up in 2010, 2011, 2012 but started to slowdown in 2013. It was normal; the computer market is dying giving way to more tablets in the hands of consumers. STX has a hard time developing new technology to follow the new trend and is struggling with a declining market where it is the leader. When I noticed this change reading financial reports, I put a stop sell at $40 while the stock was trading at $42.

What made me choose $40 instead of $35 or wait to sell it at $45? My instinct and the fact that I was happy with a 72% return (including dividends and currency exchange). I didn’t intend to sell it that fast, but the stock showed high volatility and hit $40 within a week and, unfortunately, bounced back higher up later on. Following my model, I set the stop sell based on the following:

A) The company had headed towards my expectations and realized the upside potential

B) With slow sales, the company showed the inability to continue the upside potential later on and became a risky pick

If STX would have never hit $40, I would have kept it for a while. It was just on my “sell list” to protect my gain. This is the whole idea of adding a stop sell on a winning stock: you want to make sure to cash out some of your paper profit.

To wrap it up

I never sell a stock because I make X% on it;

I sell a stock because the upside potential has materialized;

I never sell a stock because it is at its highest price ever;

I sell a stock because I don’t see how it will continue to go higher;

I use a stop sell instruction to protect my profit once I’ve decided the stock can’t reliably go higher.

But why use a stop sell if I don’t think the company could bring anything more to my portfolio? Because I may be wrong and the stock may continue to go higher! The stop sell ensures I will keep a good upside, and keeping the stock enables me to cash in great dividends in the meantime. It is as simple as that.

I’ve made a similar analysis with Husky Energy (HSE) when sales and profits stagnated and with Intel (INTC) when the company wasn’t able to show a strong ability to move toward a new technology. It’s all about companies realizing their upside potential and showing an ability to continue forward. If you made money on your trade and the company doesn’t show these two abilities anymore, just drop it and buy something else. Never look back, it just hurts!

When is the Right Time to Sell When You Lose Money

Selling a winner and realizing it keeps going up may hurt a little; but selling a loser always hurts. The question is how bad you want this to hurt your portfolio? Then again, I don’t follow books with a -10% or -20% rule either. I guess the good news is that the losing potential is limited compared to the upside potential… it can’t go under -100% hahaha!

But I usually don’t let stocks drop this far before I liquidate. My number one rule is to drop any stock announcing a dividend cut. When this happens, the company has already studied all its options and this is their last resort before everything goes sour. No one wants to remove what is taken for granted like a dividend payout without paying the price.

I’m not the fastest to pull the trigger on a bad stock either. This is mainly because when I buy shares, I believe they will go up and have more than a few headlines found on the internet to confirm my investment thesis. With a rigorous set of metrics to select a stock, I feel comfortable going through the storm and having some patience. This is why I don’t look at how much I have lost before I pull the trigger. I would rather base my decision on a more methodical approach.

A stock losing less than 10% is anecdotal. It can be tied to several factors such as a hard time for the company’s industry or simply a rough market. In fact, the stock market mood swings does not impact my decision either. I look at the company’s financial results instead. Each quarter, I look at them to make sure my main criteria are respected:

-

Dividend yield over 2.50%

-

Dividend payout ratio under 80%

-

3yr/5yr Dividend growth positive

-

3yr/5yr EPS growth positive

-

3yr/5yr Sales growth positive

-

P/E ratio under 20

If sales or EPS goes the other way; I don’t pull the trigger yet. I start by looking for an explanation. There are tons of good reasons why a company would go through one or two bad quarters. This is why it is important to be patient. Plus, as a dividend investor, I get paid to wait. But if the business model leads me to think the party is over, I will definitely drop the hammer and look for another company.

For example, I’m holding on to McDonald’s while its metrics are not the most amazing over the past 12 months. I believe in the company’s business model and think my patience will be rewarded over time. After all, I bought this stock to hold it for 10 years or more. Therefore, as long as the business is making good profits, I will not look to get rid of such a blue chip.

What really matters is to know if both sales and profits are sustainable over the long haul. As sales drive profits and profit drives dividend payout increases, you have most of what you are looking for by following only a few metrics. Then, it is important to understand what the future projects are. If the company is stagnating but working on innovations, it may worth to wait to see if this will open a new market. I would always rather wait and benefit from dividend payouts than sell each time a stock drops.

Final Thoughts on Selling Stocks

In my opinion, there are no black and white decisions when it comes down to getting rid of a stock. It all comes down to the current metrics vs the future potential of a company. If the metrics don’t fit or the potential is not there anymore, don’t bother too much and get rid of the stock. There are hundreds of great companies out there; you don’t need to stay with the ones in your portfolio forever.

Don’t sell your stocks based on a price or a percentage of gain or loss. Sell your stock because you don’t see the reasons why you bought them in the first place. Each year, I review all my stocks and verify if I can validate my investing thesis. If the company doesn’t pass the test, it’s time to sell!